Would we fix our prisons if we could see what happens inside them?

March 30th 2019 By Shaila Dewan and published here

The contraband is scary enough: Homemade knives with grips whittled to fit particular hands. Homemade machetes. And homemade armor, with books and magazines for padding.

Then there is the blood: In puddles. In toilets. Scrawled on the wall in desperate messages. Bloody scalps, bloody footprints, blood streaming down a cheek like tears.

And the dead: a man kneeling like a supplicant, hands bound behind his back with white fabric strips and black laces. Another, hanging from a twisted sheet in the dark, virtually naked, illuminated by a flashlight beam.

These were ugly scenes from inside an American prison, apparently taken as official documentation of violence and rule violations.

Prisons are the black boxes of our society. With their vast complexes and razor wire barriers, everyone knows where they are, but few know what goes on inside. Prisoner communication is sharply curtailed — it is monitored, censored and costly. Visitation rules are strict. Office inspections are often announced in advance.

So when prisoners go on hunger strikes or work strikes, or engage in deadly riots, the public rarely understands exactly why. How could they? Many people harbor a vague belief that whatever treatment prisoners get, they surely must deserve. It is a view perpetuated by a lack of detail.

But some weeks ago, The New York Times received more than 2,000 photographs that evidence suggests were taken inside the St. Clair Correctional Facility in Alabama. Some show inmates as they are being treated in a cramped, cluttered examination room. Others are clinical: frontal portraits, close-ups of wounds.

[The Department of Justice found a “flagrant disregard” for Alabama prisoners’ right to be free of cruel and unusual punishment.]

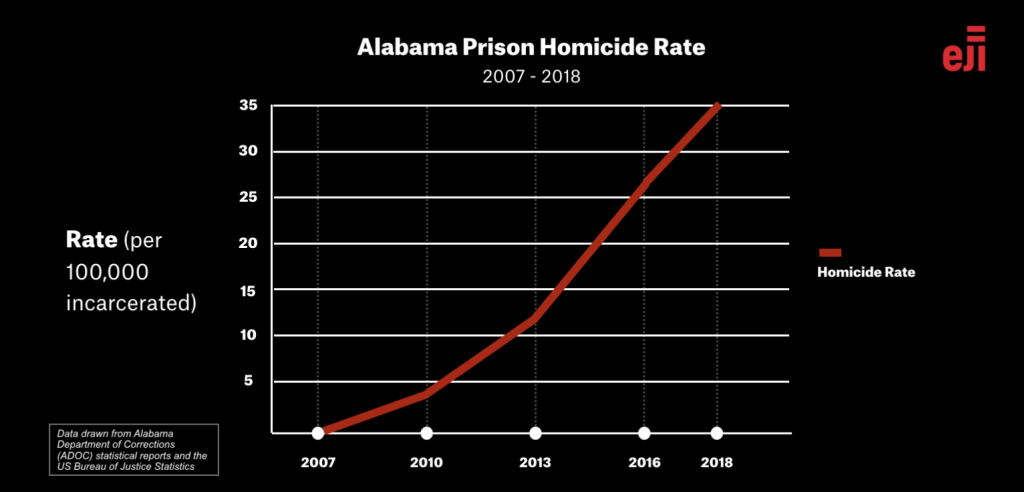

It is hard to imagine a cache of images less suitable for publication — they are full of nudity, indignity and gore. It is also hard to imagine photographs that cry out more insistently to be seen.St. Clair is the most violent prison in Alabama, which has the country’s highest prison homicide rate, according to the Equal Justice Initiative.

As I scrolled through them, shock rose from my gut to my sternum. Was I looking at a prison, or a 19th-century battlefield? Those pictured betrayed little emotion and certainly none of the bravado broadcast by their tattoos: South Side Hot Boy, Something Serious, $elfmade.

After considering the inmates’ privacy, audience sensibilities and our inability to provide more context for the specific incidents depicted, The Times determined that few of these photos could be published. But they could be described.

St. Clair is known to be a deeply troubled institution in a state with an overcrowded, understaffed, antiquated prison system. Alabama has one of the country’s highest incarceration rates and, as measured by the most recent counts of homicides available, its deadliest prisons, according to a report by the Equal Justice Initiative, a nonprofit civil rights organization in Montgomery. Suicide is epidemic as well — there have been 15 in the past 15 months.

For years there have been complaints that St. Clair inmates are heavily armed — some for self-protection — and allowed to move freely about the compound. In fact, St. Clair is more deadly now than it was in 2014, when the Equal Justice Initiative brought suit against it for failing to protect prisoners. There have been four stabbing deathsthere in seven months.

Last June, the group said the prison was failing to comply with a settlement agreement.

Prison officials dispute that, saying the Alabama Department of Corrections is committed to improving safety and security. The department has requested money to raise salaries and increase the number of officers. Multiple law enforcement agencies recently teamed up to conduct a contraband search at St. Clair that recovered 167 makeshift weapons, said Bob Horton, a department spokesman.

But as of October, the prison was still severely short staffed, with more vacancies than actual officers.

A second lawsuit, brought by the Southern Poverty Law Center, a legal advocacy group in Montgomery, says the prisons have failed to provide adequate mental health care. (The photos show a message painted on the wall in blood, with letters about the height of a cinder block. “I ask everyone for help,” it read in part. “Mental Health won’t help.”)

The photos were given to The Times by the S.P.L.C., which said it had received them on a thumb drive.

Bob Horton, a spokesman for the corrections department, said the department could not authenticate the photos.

But Maria Morris, a staff lawyer at the S.P.L.C., said the environment shown looked like St. Clair, and some photos had identifying information that corresponded to known inmates or showed men that the S.P.L.C. recognized as its clients (S.P.L.C. removed the identifying information before giving the images to The Times).

The man who painted the blood on the wall, referred to in the lawsuit as M.P., had schizophrenia and bipolar disorder and repeatedly tried to kill himself. He testified that he had been held in solitary confinement for six years, allowed to exercise one hour a day in ankle shackles.

Ms. Morris has specialized in prisoner’s rights litigation for more than a decade. She hears accounts of rape, beating or stabbing on a daily basis. I asked what it was like for her to see the photographs.

They made it impossible, she explained, to retreat into that small, self-protective corner of her mind — the place where it was possible to imagine that her clients’ stories might not be as bad as they sounded.

“Seeing what had been done to those people’s bodies — it just stripped away all of the numbing,” she said. “It was very painful to see that all of the suffering that I’ve been hearing about and trying to relate to the court — how deep it goes.”

The thumb drive included a document titled “READ ME FIRST” and claiming to be from a corrections officer. It said the photos represented only a “small portion of the injuries from inmate-on-inmate violence in the past three years.”

The writer said that the current legal agreements governing the prison stood no chance of working: “The day-to-day treatment of these men does nothing but foster anger and despair. Until major fundamental changes take place in our sentencing and housing of these men it will only continue to get worse. I can’t help but wonder if the public knows just how bad these men are treated day after day and year after year.”Testimony shows that fires in solitary confinement are common, and are sometimes used to get attention in a medical emergency.

The photos show dozens of wounded men. One had been stabbed at least 10 times. Another had a hole in his lip you could stick a pencil through. A pair of handcuffed wrists displayed 15 precise slashes. There was a recurring palette of pale red and sickly, Mercurochrome yellow. One man’s back had a shiv at least an inch wide still buried in it, right between the shoulder blades.

There were three individuals pictured in a folder called “Dead men” and seven in a folder called “Murders,” all of whom could be identified through news reports, press releases and booking photographs.

But most disturbing were the images that seemed to echo the most painful aspects of African-American history.

Many convincing arguments have been made that our penal system was at least partly designed to extend control of black people and their labor, particularly in the South, where after slavery ended black men were conscripted into chain gangs for offenses like vagrancy and “selling cotton after sunset.”

Amid the St. Clair pictures were 19 taken of a black man who was completely naked but for a pair of handcuffs, photographed from the front, back, left and right. In one frame two white officers, standing guard inches away from him, avert their eyes.

Another image brought to mind the photos of the monstrously disfigured face of Emmett Till, the teenage victim of a 1955 lynching in Mississippi, which galvanized the civil rights movement when they were published by Jet magazine.

Though separated by more than half a century and by a wide gulf in circumstances, the St. Clair photos showed another mutilated, African-American face, this time belonging to Emory Cook, a 54-year-old prisoner killed in a cell three years ago. Under Alabama’s harsh version of a three-strikes law, Mr. Cook had been serving a life sentence for third-degree burglary.

As a prisoner, he was entitled to be protected from harm. He looked like he had been hit with a plank.

Correction: April 1, 2019 An earlier version of this article misidentified the location of the Equal Justice Initiative, a nonprofit civil rights organization. It is in Montgomery, Ala., not Birmingham.

Shaila Dewan is a national reporter and editor covering criminal justice issues including prosecution, policing and incarceration. @shailadewan

You must be logged in to post a comment.