Sam Levine in Tuscaloosa

Thu 27 Feb 2020 17.30 GMT First published on Thu 27 Feb 2020 11.00 GMT

The fight to vote – Alabama

Alfonzo Tucker Jr is just one of millions of Americans who have been entangled in a racially biased system – and deprived of their democratic right

In 2018, with the midterm elections approaching, Alfonzo Tucker Jr was particularly eager to vote. The mayor of Tuscaloosa, Alabama, Tucker’s hometown, was running for governor, and the year before he had canvassed for Doug Jones, a Democrat running in a closely watched US Senate race.

But Tucker wasn’t able to cast a ballot – state officials refused to even let him register. It wasn’t until weeks later that he learned why he had been deprived of the right to vote.

He owed the state $4.

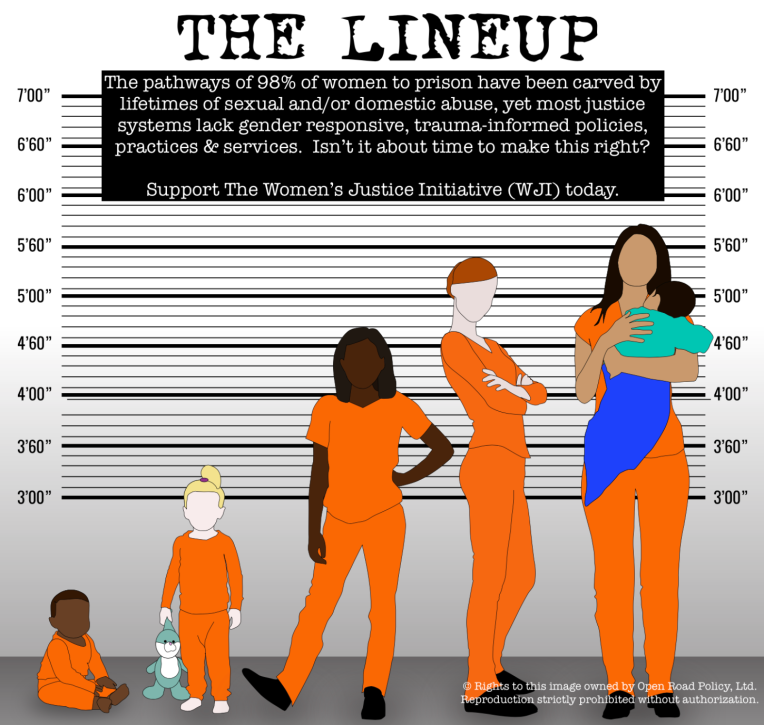

The US is founded on the promise of democracy and fair representation, but it is also the country where minorities are frequently disenfranchised for political gain. Among the most vulnerable are millions of Americans, disproportionately African Americans, like Tucker, who have been entangled in America’s racially biased criminal justice system, and lose civil liberties like voting as a result.

The barriers facing Americans like Tucker, advocates say, are modern adaptations of poll taxes and other devices which were designed to keep people from the voting booths during the Jim Crow era – when white politicians used the law to curb the civil rights of African Americans. Alabama is one of 30 states that requires people with felony convictions to pay back the financial obligations associated with their sentence before they can vote again.

Tucker’s case is particularly glaring. He lives less than a hundred miles north-west of Selma, the birthplace of the voting rights movement in America. This week, civil rights leaders are commemorating the 55th anniversary of the Selma to Montgomery marches led by Martin Luther King Jr and civil rights activists as they protested against laws preventing African Americans from voting. Many were brutally beaten in Selma during the protests.

The specific policy that had ensnared Tucker dates back to the turn of the 20th century when Alabama leaders, openly seeking to preserve white supremacy, stripped anyone convicted of a crime of “moral turpitude”, among other offenses, of the right to vote.

“What is it that we want to do? Why, it is within the limits imposed by the federal constitution, to establish white supremacy in this state,” John Knox, the chair of the convention, said at the time. “If we would have white supremacy, we must establish it by law – not by force or fraud,” he added.

Tucker said the legacy of that discrimination affects the lives of people like him today.

“I read about the challenges during the 60s, 50s, that black people had to overcome just to vote,” Tucker said. “It’s the same thing going on in 2020.”

Tucker, who sometimes goes by Zo, speaks softly and deliberately. He has lived in Tuscaloosa his whole life, now in a modest house 10 minutes outside of downtown. He says he would have left the city where he grew up, but never had the money.

Sitting in his living room, surrounded by pictures of family, Tucker said things are much different now for him than they were in the early 1990s, when he was much more “aggressive”. In the late 1980s, he got into a fight at a club with a University of Alabama football player and wound up being convicted of third-degree assault, a misdemeanor. A few years later, he fought with a police officer and was convicted of second-degree assault, a felony. He wound up going to prison for two years and serving several more on probation.

After he got out of prison, Tucker rebuilt his life, working at steel factories and in maintenance, and chipping away at the approximately $1,600 that the court had ordered him to pay. He had two more children, which made him want to stay out of trouble. He joined the Nation of Islam.

Before his conviction, Tucker had never voted. But in prison, Tucker had read about Medgar Evers, who fought for equal citizenship and was assassinated in Mississippi in 1963. When he got out, he started regularly voting in elections. He and his wife Narkita would bring his young children into the voting booth with them, wanting to teach them about the importance of a single vote, and the long struggle African Americans had faced to gain access to the ballot.

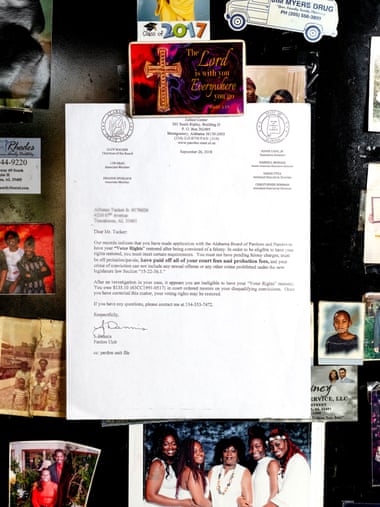

But in 2013, Tucker got a letter from his state officials saying he could no longer vote.

He was angry and upset, but didn’t act immediately – the letter didn’t tell him anything about how to get his voting rights back. Then came another letter, a few years later, this time addressed to his son, Alfonzo Tucker III, who had just turned 18, and claiming that he too was ineligible to vote. The younger Tucker, however, didn’t have a criminal record. It was a mistake, possibly because he shared his father’s name.

Tucker got his son registered to vote, but the episode lit a fire in him. As the 2018 midterm elections approached, he went to an event where activists were helping people with felony convictions learn about their voting rights, and called up the Alabama board of pardons and paroles to talk about his case. Two weeks later, the board sent him a letter saying he still owed $135.10 in connection with his conviction.

Tucker, who relies in part on disability income, borrowed money from his sister to pay off the debt. But just when he thought it was settled, a courthouse clerk told him he owed money for another decades-old criminal offense – an additional $5,535.47 which she said he had to pay back to gain back his vote.

Faced with the staggering amount, Tucker contacted Blair Bowie, an attorney at Campaign Legal Center, a Washington DC voting rights group. It took Bowie 15 minutes to realize Alabama officials made a huge mistake.

Under Alabama law, people with felonies only have to pay off the money originally assessed as part of their criminal conviction to regain their voting rights. By 2018, Tucker had paid back most of what he owed. But, unbeknown to him, the state had added an additional debt of $131.10, a fee that was irrelevant to whether he could vote because it was not part of his original conviction. And the $5,535.47 debt was from a misdemeanor offense, Bowie saw, which does not cause someone to lose their voting rights in Alabama.

All that Tucker actually owed in order to vote was $4.

“What is voter suppression if not officials wrongly telling you that you can’t vote?” Bowie said. “That’s been a classic way of disenfranchising people, particularly in Alabama.”

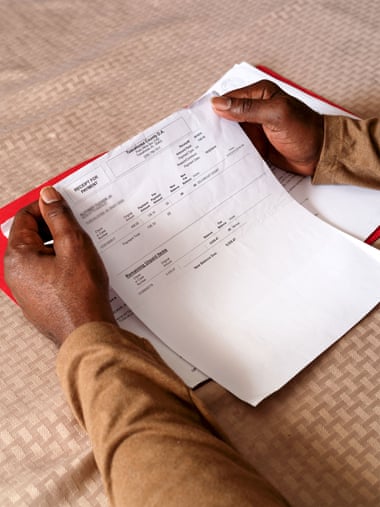

After he paid the $135.10, Tucker drove two hours to Montgomery, the state capitol, with a friend to hand-deliver the receipt to a staffer at the board of pardons and paroles.

Alfonzo Tucker holds his receipt for payment showing he paid the amount owed to restore his voting rights.

Facebook Twitter Pinterest Alfonzo Tucker holds his receipt for payment showing he paid the amount owed to restore his voting rights. Photograph: Johnathon Kelso/The Guardian

But weeks later he had not heard anything back. The elections came and went, and Tucker couldn’t vote. The parole board declined to comment on Tucker’s case.

Bowie eventually referred Tucker to John Paul Taylor, an organizer with the Southern Poverty Law Center, who followed up with the board and got Tucker registered to vote in 2019.

Bowie and Taylor said Tucker shouldn’t have had to rely on experts to get his voting rights back.

“Here’s a very clear example of a person who has jumped through every single hoop that you’ve given them and they’re still being denied because of something that they really don’t even know about,” Taylor said.

Meanwhile, Tucker and Bill Foster, the friend he went to Montgomery with, helped start a group in Tuscaloosa to assist people with felonies get their voting rights back. Tucker’s story helps people understand that they can in fact vote once they complete their sentence, said Larry Tucker, his cousin. And Alfonzo said he’s met other people who have wrongly been told they owe the state money.

So far, Tucker estimates that they’ve been able to help about 10 people – people like Terrance Gray, 49, who learned he was eligible to vote last year. Gray believed he had been ineligible to vote since he was released from prison in 1996.

“He told me that it will make a difference if more people go and vote,” Gray said of Tucker. “He’s always been on me about that.”

Tucker plans to cast his first ballot since the ordeal this year (he says he likes Bernie Sanders). He thinks the state should give him back the extra $131.10 that he paid.

You must be logged in to post a comment.